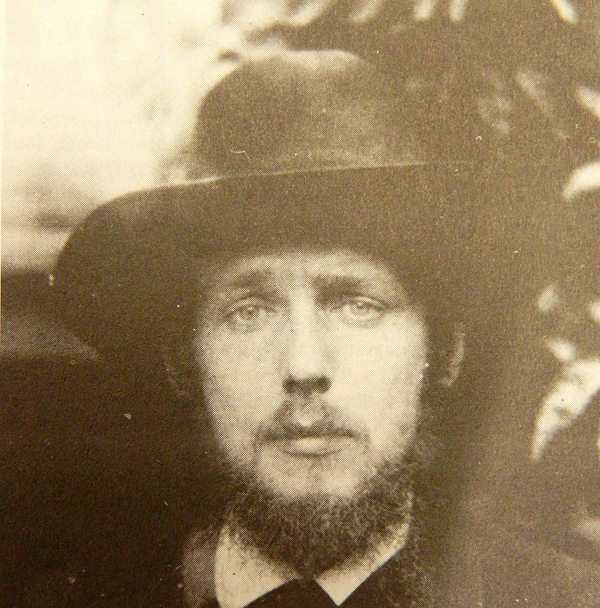

Arguably there would be some very good reasons not to write a biography about Dr Thomas Fauset MacDonald (1862-1910), a Lanark man whose politics veered from a long-running association with militant anarchism to becoming one of the “pioneers of the White Australia movement,” according to his obituary in the British Medical Journal.

But the fact is this utterly bizarre figure, whose historic racist lobbying within the Australian labour scene continues to help cast a baleful shadow over that country’s politics, unlocks a part of the anarchists’ history — and for all the brevity of his direct involvement he had a substantial impact. So without ignoring the monster, it is worth examining the doctor.

Born to Thomas and Jane MacDonald, Fauset (he used this for his pen-name) grew up the son of a successful GP and followed his father into the profession, graduating in medicine and surgery from Glasgow University in 1882. He sailed to Australia and New Zealand in 1883, spending six years becoming a specialist in tropical diseases and contributing several reports to medical journals at the time. In 1889 he returned to Britain and began studying for a veterinary degree, which he achieved in 1892.

At this point, aged 30, there appears little to suggest that he was particularly politically active, having followed a vaguely interesting but not terribly noteworthy path through the medical profession and achieving much the same middle-class position as his parents before him. He seemingly hadn’t made contact with the anarchists, as it was noted by David Nicoll (of whom more later) that Fauset only “came into the movement in the summer of 1893,” spending money freely and “in favour of the most violent action.” It is unclear exactly what sparked his conversion to the cause.

From zero to hero

Fauset certainly made a splash in his first few months of activism, bringing funds, expertise and his travel bug to a movement that was constantly on its uppers. His apparent first ports of call were with middle-class socialist elements and Russian exiles, then moving on to correspondence with Peter Kropotkin and contact with the Commonweal and Freedom groups.

Olivia Rossetti paints a glowing portrait of the early involvement of Fauset in the socialist and anarchist sets in her book A Girl Among the Anarchists. As teenagers, the Rossettis published anarchist paper The Torch out of their father’s basement, and Fauset appears to have contacted them at some point in 1893, shortly after they had acquired a printing press — his name began appearing as a contributor in June of that year. By 1894 he was the publisher.

While semi-fictional, Rossetti’s novel refers to numerous figures from around the time, and Fauset in particular gets a hefty role under the moniker “Dr Armitage.” Writing of her first meeting with him, she describes attending a “small and stuffy” parlour room belonging to Nekrovitch (actually the Russian nihilist Sergey Stepnyak-Kravchinsky), mostly bare of furniture but full of well-connected and cosmopolitan people. Russian exiles, British liberals, socialists and Fabians mixed with “journalists and literary men whose political views were immaterial … all manner of faddists, rising and impecunious musicians and artists—all were made welcome.”

Throughout the book, she compares him favourably with what she perceived to be a gruff and often lazy community of anarchists:

Dr. Armitage was one of the most noticeable figures in the English Anarchist movement, and it was with him that I first discussed Anarchist principles as opposed to those of legal Socialism

…

Dr. Armitage was a fanatic and an idealist, and two convictions were paramount in his mind at this time: the necessity and the justice of the “propaganda by force” doctrine preached by the more advanced Anarchists, and the absolute good faith and devotion to principle of the men with whom he was associated … Not for a single instant had Armitage hesitated to throw open the doors of his Harley Street establishment to the Anarchists: to him the cause was everything, and interests, prudence, prospects, all had to give way before it.

It’s easy to see why the politically-minded teenager might have gotten on with Fauset in 1893. In among a variety of dilettante London worthies and heavily bearded international hardliners the handsome 31-year-old doctor, as thoroughly middle-class and mannered as she, appears to have been gregarious, enthusiastic and genuine, friends with eminent figures and a member of the Freedom and Commonweal groups. He was especially connected with the latter by May 1st of that year, acting as financial backer (with Max Nettlau) to Commonweal during the editorship of tailor Henry B Samuels.

The appointment of Samuels as acting editor had been controversial. Stridently anti-trade union, he was of the opinion that Englishmen — and only Englishmen — should be free to blackleg. Along with a strong position in favour of propaganda of the deed (ie. terror to “wake up the people”), which comrades of the time such as Max Nomad noted always seemed to involve action being taken “by others,” he seemed an odd choice to follow publisher Charlie Mowbray and former editor David Nicoll, who had both been jailed for 12 months in connection to the Walsall bombing plot. He was however very much on Fauset’s wavelength, and when Nicoll tried to regain his editorship in December 1893, he found Fauset blocking the way:

Tom Cantwell acted as porter and excluded all ‘possible disturbers’. The usual pretext was they were ‘not members’ of the ‘Commonweal Group’. Most London Anarchists were not, the Commonweal Group consisting of about a dozen members ( … ) If however a man’s principles were alright, i.e. if he were a friend of Mr Samuels, they let him in. Besides the benefits of ‘scientific packing’, Mr Samuels had the advantage of the official support of the Freedom people. There were two delegates present – Agnes Henry and Dr Macdonald. Miss Henry was neutral, Dr Macdonald supported Samuels with enthusiasm ( … ) Seeing how everything had been ‘arranged’ I threw up the editorship.

The recollections of George Cores note that throughout his tenure: “Samuels’ conduct was deplorable, and led him open to the gravest suspicion. The police took no action against him.” John Quail offers a slightly different view in The Slow Burning Fuse, noting that “he had served his time and played his part sufficiently well to be trusted by sections of the movement” but also quoting contemporary Louise Sarah Bevington, who knew him well, saying “the keynotes of his character are vanity and vindictiveness.”

Though there are suspicious elements to Samuels’ time in the movement, Quail notes that no more than circumstantial proofs were ever offered that he was anything other than an anarchist. What is certainly true however is that Samuels ran a paper that was dedicated to a spectacular and insurrectionist approach, which inspired Fauset to keep his wallet open seemingly until shortly after Samuels was deposed in June 1894 under suspicion of being a police ringer. Funding dried up just a month later, and Commonweal closed that August.

The Greenwich Observatory Bombing

The catalyst for Samuels’ demise as editor was amongst the more noteworthy in this period of the British anarchist movement’s history, warranting two entire chapters of John Quail’s book.

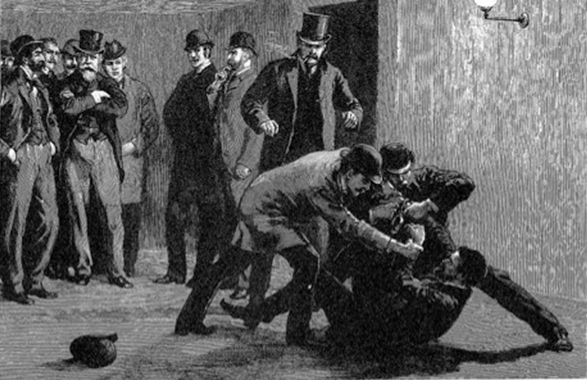

On February 15th 1894, an explosion near the Greenwich Observatory drew a park keeper, who found Martial Bourdin, severely wounded by the bomb which had gone off while he was carrying it, blowing his hand from his wrist and opening his belly. Bourdin died hours later, saying nothing about his accomplices, but suspicion was rife across the movement, with Samuels quickly put in the frame for having potentially provided the explosive materials. He was a Bourdin’s brother-in-law and had been seen in Bourdin’s company on the day of the attempted attack, yet was not even interviewed, let alone arrested — and a justifiable paranoia was growing within the anarchist ranks.

The movement had come under intense pressure from the public in the aftermath, with an angry mob attempting to overturn Bourdin’s hearse during the funeral march and anarchist events being attacked by reactionary elements, including direct action from police to disrupt anarchist organising, both covert and overt. May 1st saw police-led attacks against public anarchist meetings.

In this atmosphere, Samuels was busy bragging about his links to Bourdin. Then, at the end of May, David Nicoll (who was holding a grudge against Samuels over his ongoing editorship of Commonweal) reported a story where Samuels had come good on a boast that he could lay his hands on sulphuric acid to another tailor by handing him a small vial of the substance — the other man’s house was raided two days later.

At a subsequent meeting, Nicoll relates, Samuels was confronted over his handing out of acids and his links to Bourdin, and admitted both, subsequently being expelled from Commonweal. In mounting his doomed defence however, Samuels noted that he had acquired most of his materiel from the stocks of his good friend Fauset MacDonald.

There is a direct parallel in the report of this confrontation by Nicoll and a scene in Rossetti’s novel, in which she describes Armitage/Fauset as being shocked by Samuels’ admission. Whether he actually spoke to her on the subject or not is unknown, but her characterisation is as follows:

After some seconds’ hesitation Armitage [Fauset] replied: “I do not desire or intend to go into any details here concerning my past conversations or relations with Jacob Myers [Samuels], neither do I consider myself in any way bound to discuss here the motives which prompted, or which I thought prompted his actions, and the requests he made of me. As Anarchists we have not the right to judge him, and all we can do is to refuse to associate ourselves any further with him, which I, for one, shall henceforth do. The knowledge of his own abominable meanness should be punishment enough for Myers.

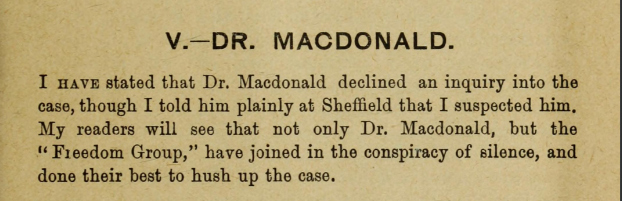

Fauset could not entirely disassociate himself from the situation however, inasmuch as he had also found himself in Nicoll’s line of fire. For Nicoll, Fauset was as much to blame for the Greenwich debacle and the subsequent police crackdown as Samuels and Bourdin, acting as a silent partner in providing the explosive chemicals, and he said as much when the doctor visited him in Sheffield a month later:

Certainly it was true that Freedom hadn’t backed Nicoll in the case, much as it hadn’t covered his activities since his release from prison, and it seems plausible that Fauset could have used his connections through Freedom to outmanouver Nicoll in the broader movement, as Nicoll was already by this point considered something of a crank by many senior voices, including Kropotkin and Max Nettlau. Fauset’s willingness and ability to travel brought him a wealth of contacts across the country, allowing him to take on a tour of Dublin (April 1894), Sheffield (June/July 1894) Leicester (July 1894) and Manchester (late 1894). By August, Nicoll was being accused of having “spy mania” by John Turner and pressed to cease publishing screeds accusing Samuels and MacDonald.This was partially successful, as after his initial accusations Nicoll remained silent until 1897, by which time Fauset’s anarchist boat had long since sailed.

The ‘other’ Commonweal

It’s worth a brief diversion to look at Nicoll’ belated summary of events, which involved the distribution of an inciendiary pamphlet entitled The Greenwich Mystery and an issue of Commonweal entirely unrelated to the defunct former publishing group. The full extract is quite long and can be found at this forum thread, but in summary Nicoll believed Fauset had:

- Encouraged the most violent of actions while remaining himself above the fray

- Funded (and by implication controlled) Commonweal

- Provided a “small arsenal at his dispensary” (and hinting that these materials had been deliberately left for Samuels to pinch) including sulphuric acid and chlorate of potash, both of which found their way into Bourdin’s bomb

- Alongside Samuels, avoiding police interest in a quite baffling way (implying he was a nark)

He also describes the series of events directly after the bombing, when MacDonald visited him in Sheffield:

When the news of the disclosures at the “Commonweal” Group reached Sheffield, Macdonald came down with a young comrade from Manchester, and did his best to persuade me to make no disclosures in the Anarchist. He said he was firmly convinced “Samuels was not a police agent.”

“But, MacDdonald, ‘ I said, “how could he have stolon that stuff from your surgery without your knowledge, and why did you lot him go on stealing more!”

“Would you stop a man from acting on his own initiative” said the worthy doctor.

“ Yes, I mean to stop that kind of business. Don’t you know he was exposing you to terrible peril, and why did you not stop him? If violence is necessary, let it come in the form of open insurrection, and not in dynamite explosions.”

I looked round, and saw the doctor shaking bis head with a pitying smile to his young companion. I then spoke with some warmth.

“Don’t you see,” I said, “that your own conduct İs open to grave suspicion?”

“Now, if you talk like that,” said the doctor, “I shall…-“

“Don’t try it on. MacDonald,” I said.

He replied with a seraphic smile.

MacDonald left Sheffield after obtaining from me a promise that I would publish nothing more on consideration that there should be a full and fair inquiry into the case by a proper committee consisting of delegates from all the London Groups. That inquiry never came off, the doctor informing the young man from Manchester, who was acting in good faith, that comrades in London took no interest in the matter, and if the inquiry was held no one would attend. This is not true, for my pamphlet has been eagerly bought by the London Anarchists. So Mr. Samuels’ accomplice did his best to hush up the case. MacDonald soon after left England, and has never returned.

At the annual meeting of provincial Anarchists at Monsal Dale Mr. Banham, who defended Samuels, told us a story which showed Macdonald’s real opinion of his accomplice. Banham related how that after Samuels had given the men the chlorate of potash and

sulphuric acid, at his suggestion they tried an experiment, but the stuff would not ignite.

MacDonald was asked at Manchester for an explanation. He said, “Samuels was so ignorant of explosives that he had probably taken cough mixture for sulphuric acid.”

…

Though MacDdonald’s name was freely mentioned before an audience of about eighty people, some of whom wore not Anarchists, as the man from whom Samuels had “stolen” the explosives, yet, though he stayed in England some weeks afterwards, the police never arrested him or Mr. Samuels.

Nicoll was roundly condemned for his troubles by the Freedom Group in particular, members of which called his mental health into question and castigated him for laying into MacDonald in the doctor’s absence. George Cores, who maintained cordial relations with Nicoll until the older man’s death in 1919, noted sadly that:

In the concluding years of his life I often met him and I am gratified with the firm conviction that he regarded me as a true friend and comrade till his death, though he was suspicious of so many about him.

The restoration of the Editorship would have saved him from very much mental, moral and physical suffering.

He was truly a martyr. The wretched, petty, greedy vanity of a man was a greater blow to Nicoll than anything the enemy could do, and made the concluding phase of his life a tragedy. No man ever lived who was more idealist, more concerned with the freedom and welfare of humanity than David J Nicoll.

Fauset meanwhile was already far from the fray as Nicoll duked it out with the likes of Nettlau and Turner. He seems to have left for Australia at some point between August and October of that year, to seek a new life omitting bombs and fractious British anarchism.

The white supremacist anarchist

It’s possible that Fauset entertained some racist thinking before he began his long boat ride to the other side of the world — his good friend H B Samuels was certainly of the opinion that Englishmen were of superior stock and “racialism” was hardly uncommon at the time. He seemed to hold no particular grudge towards the Irish however, as he happily went to talk in Dublin in 1894, shortly before he left, at a time when anti-Irish prejudice was rampant. His attitude towards his hosts was approvingly cited in the local press:

He is a Scotsman, cool and shrewd in manner. Not once, even when closely “heckled,” as they would say in his own country, did he show any sign of heat. His arguments may be put thus. He objects to any form of artificial government to begin with: but he would not remove our governors by the summary method of lifting them into the air in so many atoms. He desires to remove Parliament by a natural and constitutional process. To workingmen, he says, absorb the “blacklegs,” form free associations, let those associations associate with other associations, and go on developing in this manner until great international federations are established … the lecturer is a great believer in Darwin’s theory of evolution, and referred to this subject frequently to enforce his arguments.

At this point in his life he appears to have been in favour of an internationalist approach, but was also prone to looking at life through the lens of evolutionary theory — sometimes a precursor to the developing of a “social Darwinist” outlook and not unacquainted with racism towards non-Europeans.

His interest in the supremacy of the white race however only bloomed into full-fledged activism during his time in Australia, opening the oddest chapter in Fauset’s exceedingly strange political journey — one which suggests he was never a mole, for what logic would send a police undercover from the heart of anarchist London to a Australian frontier town in order to found a racist class struggle movement?

But this bizzare project would eventually drive Fauset’s politics in the latter years of his life, and while his two years in London were hidden from the British Medial Journal’s obituary writers, who instead were fed (or made up) a cock-and-bull story about a two year medical studying jaunt around Germany, America, Italy, Egypt, China and Japan, his efforts to “pioneer the White Australia movement” were officially documented.

He settled, initially, in Queensland, where he initially made his name as a vet, dealing with a tick epidemic in 1895-6, but seems to have also tried to immediately immerse himself in radical circles around Sydney. Joining the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science (Aaas, now Anzaas) he wrote for Sydney’s The Worker in 1896 on “the social question” castigating the iniquities of government, opining that “the laws of the universe are anarchical” and expressing his admiration for the Surplus Labor League.

The next year, he delivered a paper to the Aaas on Kropotkin’s approach to anarchism, and then moved around 2,300 miles north as the crow flies to set up a cottage hospital at Geraldton (now Innisfail) — Dr T. F. MacDonald’s Bureau of Tropical Disease and Cottage Hospital.

The outback village could not have been further away from the electric, seething paranoid circles he had frequented in Britain. Settled as a post office site just 25 years prior, Geraldton wouldn’t have its own paper until 1906 and even today contains just 9,000 people. This was the town in 1885:

Due to a goldrush in the surrounding area, it did become a more multicultural place than most while Fauset lived there, with First Peoples and Anglo-Celtic settlers quickly being outnumbered by “Kanaka” South Sea Islanders. Aboriginal and Torres Strait workers, Chinese miners who developed the banana industry and retail businesses, French merchants, and German timber and sugar producers — though the most influential Italian influx wouldn’t happen until Fauset had moved on.

It is possible that Geraldton was where he first developed the disdain for non-English peoples that would lead to his embrace of eugenics. He certainly had a difficult time at the colony, struggling to deal with a hookworm infestation which he found “deeply rooted and flourishing among the inhabitants of the Johnstone River District.” Nine out of ten children were infected, and MacDonald recorded a trend for them eating dirt as an “irresistible craving,” saying that such children became pale, disobedient, cunning, dishonest and immoral. Affected adults meanwhile he believed to have developed an extreme fondness for pickles, curry and alcohol and were lazy and aggressive. His requests for help to stamp out the infections in 1900 were ignored by the Queensland government as sensational nonsense.

Fauset refused to give up however, and the nearest larger town to Geraldton at that time was (and largely still is) Brisbane, so it was to the Brisbane Courier that he wrote in 1903, complaining again about the “earth-eating” disease. It appears that 1903 is the same year he was swayed to the cause of eugenics.

While she gets his place of birth wrong, Diana Wyndham’s description in her thesis Striving For National Fitness of “Tom” F MacDonald, a Queensland doctor running a 30-bed hospital in a “north Queensland town” from 1896-1906 could hardly be anyone else, and she gives an insight into his movements in those years:

In January 1905 he wrote to Francis Galton at the Eugenics Record Office in the UNiversity of London to enquire about his Eugenics fellowship and to offer himself as an applicant. He explained that he had read about it in an Australian paper, which appears to be the first reference to eugenics in an Australian newspaper. His application included a reference to a paper (renamed “Evolution and Sociology”) which he had read at congresses in 1903 and 1905.

Fauset noted to Galton that he would have to keep his interest off the written page, as he hoped to sell articles to the London press on the subject in due course, but his interest clearly extended to his organising and speaking activities, as he would would go on to flat out argue the case for Eugenics on the basis of increasing white control of labour in his 1907 book Experiences of ankylostomiasis in Australia. In it he suggested that southern Europeans were particularly vulnerable to hookworm infection (ie. laziness and fighting), and noted approvingly that “South Sea Island, and other coloured labour generally, has been replaced by workers of our own people in fulfilment of the national ideals of ‘White Australia’ … the Caucasian skin has been presented with an opportunity of proving its power to survive.” He really was off the deep end by that point — not even kidding, he’d patented a diving suit in July 1906.

New Zealand, London, and Africa

By the winter of 1906, Fauset had had enough. At some point between July and November he upped sticks and got on a boat headed East, to New Zealand, arriving in Wellington in time to be the guest speaker of the Socialist Party there at an event advertised, suitably, by their party paper — Commonweal:

A visiting speaker from Australia, Dr T F McDonald, ‘also referred to the US Governmental conspiracy which led to the judicial murder of Parsons and his comrades’, before proceeding with his prepared speech on the philosophical inheritance of Kropotkin, Bakunin and others.

A noteable thing about the writeup is that Fauset clearly still felt himself to be in touch with the anarchist movement while he was pursuing his Rights for Whites campaign in Australia. In Sewing Freedom: Philip Josephs, Transnationalism & Early New Zealand Anarchism, Jared Davidson looks into this period of his life:

When he arrived in New Zealand, the London ex-pat “introduced himself to the then Honorary Secretary of the Wellington Branch of the Socialist Party as an anarchist communist,” and energetically engaged himself in the scene. Macdonald’s “clearness of vision” and “honesty of purpose” was put to good use.

As well as lecturing on behalf of the Discharged Prisoners’ Aid Society, he gave numerous talks on socialism and anarchism, published a number of medical pamphlets and regularly penned articles in the Commonweal, such as “Humanist Interpretations of Crime”; “The Prime Minister” (a satirical text mocking those in power); and “Freedom and Union”—“the principles which provide the anarchist-communistic ideal of a freely federated humanity.”

In late 1906, he toured the country advocating for an Imperial Labour Conference in London, which was warmly approved of in a printed address to Macdonald delivered by “representatives of the labour movement, the Socialist Party, and others interested in the economic advances of the masses.” The undersigned recognized “the enormous potentialities of a gathering of Labour representatives,” and added, “we believe the seed you have sown amongst us will grow.” His activity eventually caught the attention of conservative cartoonist William Blomfield, who put ink to paper in order to ridicule Macdonald’s revolutionary politics.

But eugenics were never far from the surface for Fauset after 1903, and alongside keeping up a steady stream of racist writings. Davidson notes:

Numerous press interviews, pamphlets, and letters to Nettlau [from the time] are rife with discriminate statements that betray his racism. The labour question in the antipodes, wrote Macdonald, faced “the element of cheap, coloured, absolutely servile alien labour… with the presence of Japanese, Chinese and other eastern peoples, the workers of Australia have had an extra battle to fight.”

Indeed MacDonald, still friends with Peter Kropotkin, wasn’t afraid to push his line internationally. In a quite extraordinary rant published first in Freedom and then in Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth in 1907 [PDF pp. 405-410], he argued that:

For some 30 years the work in tropical agriculture fell entirely into the hand sof cheap alien workers, who were in reality slaves, having neither social privileges extended to them, nor could they in their helpless ignorance form even the simplest institution of of self-defence. In the mines, Chinese labour had to be opposed.; in the pearl fisheries, the Japanese.

With some pride he goes on to argue that white Australian labour had successfully forced out this “hydra-headed enemy” before decrying its fall into parliamentarianism. It appears that Mother Earth made less fuss (this was a magazine that actually carried adverts for the American Journal of Eugenics in the same edition) than the New Zealand Socialist Party, whose members slated him and called him out for lying about having acquired their official recommendation in the first place. He fell out of favour with the group and was officially declared persona non grata in July 1907, the same month in which he set up the White Race League, placing himself as president.

Fauset’s presidency was shortlived however, and with the humiliation of yet another public rousting from erstwhile comrades looming, he once again took his heels to the other side of the globe — by September he was back in Liverpool, taking in a whirlwind tour of his old mates (including a visit to Kropotkin in Paris) before returning to Britain to bring the Good News of socialist eugenicism.

For the next two years he appears to have toured, spoken, and in 1909 he published a book of verse, North Sea Lyrics. In 1910 he took up a post with Compagnie de Kong in San Pedro, Ivory Coast, and worked there until his death from yellow fever on December 14th, aged 48.

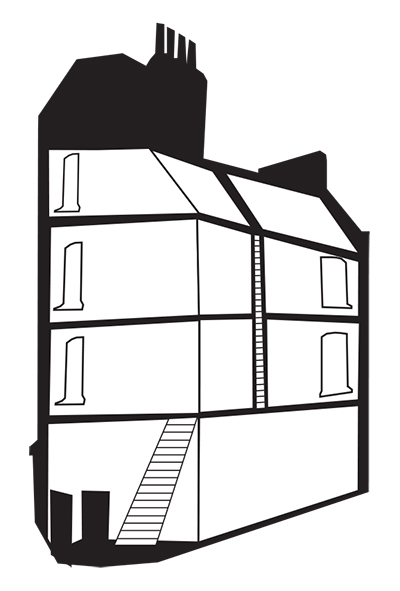

This article was written as part of a fundraising drive for works at the Freedom Building, which currently hosts no less than nine anarchist and campaign groups in central London. All of the groups involved work on a shoestring budtget, so while we collectively cover year-on-year costs, we need a bit of help to keep the roof sound! There’s details on how to donate at the top of the page, any pennies would be appreciated.